ARE WE NATURALLY VIOLENT?

Most of my own research until now has been on the subject of violence in the Middle Ages. It's a topic a lot of people are talking about at the moment, and even more so now with the publication of Steven Pinker's Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined.

This is an extremely provocative, and wonderfully wide-ranging book, in which Pinker (a cognitive scientist) argues that levels of violence have declined over the centuries. Given the mass violence of the twentieth century, and our seeming inability to relinquish war (see, for example, here), this is not uncontroversial. Equally problematic is Pinker's reliance on other people's interpretations of the past, without checking the sources or distinguishing between different kinds of evidence.

But it's a really seminal book, and one which really makes us challenge our approach as historians. In a way, the really important question about violence isn't whether it has declined (the surviving sources make it very difficult to construct reliable comparative statistics), but why it happens.

Most historians now, myself included, have tended to approach the problem from a cultural perspective. We look at how education, religious discussions, political discourse, moral frameworks and so on, shape the ways in which people get involved in, and interpret, acts of violence. But there's a real problem here: in talking endlessly about cultural constructs, we shy away from the very uncomfortable truth that in order to have been quite so prevalent throughout history, there must be something violent embedded in our human nature.

Pinker, as a behavioural psychologist, is particularly interested in how this violent nature has been, in a sense, tamed over the centuries - the processes by which our 'better angels' come to the fore. He cites the role of the state, commerce, female values, empathy and reason. All this sounds to me very convincing and nicely intertwines cultural and socio-political changes with an acknowledgement of our human nature.

By implication, though, Pinker is suggesting that the Middle Ages were an era of irrationality, when people lacked a sense of moral reason, when 'macho' values ruled supreme. As any medievalist knows, this is far from being true of the period.

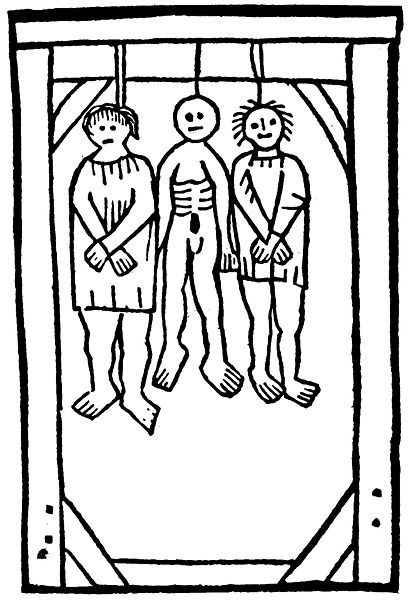

Pinker claims that medieval people saw violence so often that they were largely inured to it, but looking at the sources, whether literary or legal, paints a completely different picture. For example, Francois Villon's fifteenth-century French 'Ballad of the Hanged Men', describes how 'We are never ever still: This way and that way, as the wind blows, It sways us at its whim, And we are pecked at by birds more even than thimbles.'

The tone is one of pathos, and the poem only achieves its dramatic effect by appealing, precisely, to the empathy, of the audience - that characteristic which Pinker denies to pre-modern peoples. And if this was an era lacking moral reason, why did preachers and moral arbiters in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries engage in such long discussions about the justifiability of domestic violence? They found it profoundly problematic and were unwilling to condone it in any straightforward way. If this was an era where the 'state' had no role to play in curbing violence, why do we find legal records at all, and why do we find contemporaries appealing to royal government to practise what it preached in terms of legal constraints on violence?

My point is not that the Middle Ages weren't as violent as Pinker suggests. They may well have been. But it certainly was an era during which people thought long and hard about the implications of violence, and when people were genuinely concerned and shocked about it. And it's surely in acknowledging rather than denying the complexity of medieval thought on the question that behavioural sciences really add something to our understanding. These aren't just cultural issues, but questions which make us think about human nature and where psychologists and historians can really learn from each other.

For an excellent review of this material, see G. Hanlon, 'The Decline of Violence in the West: From Cultural to Post-Cultural History, English Historical Review (2013), 128/531, pp. 367-400.

No comments:

Post a Comment