Miraculous Images

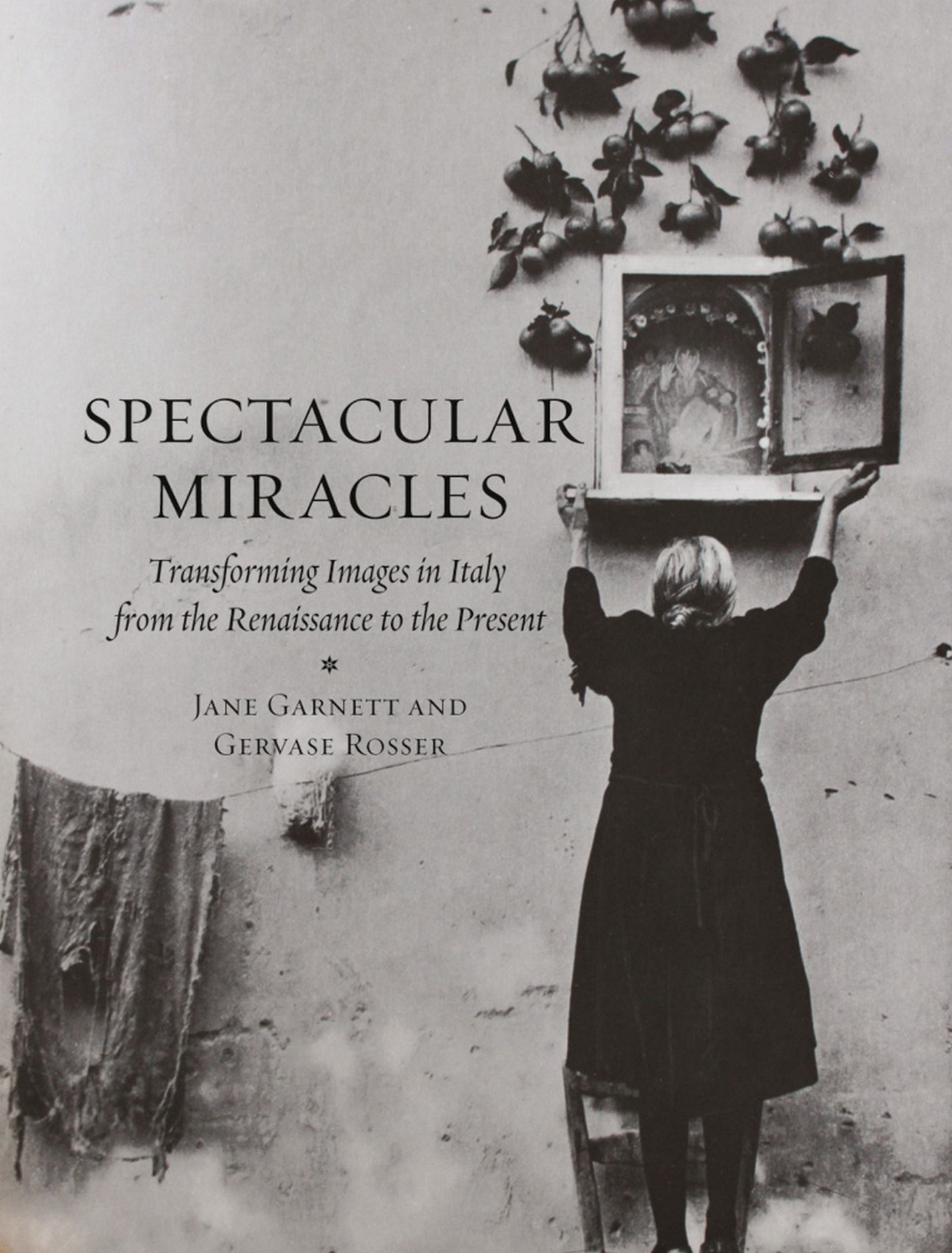

I've just finished reading Jane Garnett and Gervase Rosser's new book, Spectacular Miracles: Transforming Images in Italy from the Renaissance to the Present.

The book is about the history of images which were, and often are, thought to work miracles on behalf of their viewers. The idea is such an intriguing one, and extremely prevalent, as Rosser and Garnett show, with some wonderful and very moving examples of miraculous images from medieval and modern Italy. From an anthropological perspective, the images often seem to function as meeting-points of faith and community, of popular devotion and hegemonic prescriptions and, more often, proscriptions.

Most thought-provoking, I thought, were the implications for how we think about images. Rosser and Garnett point out that many of these miraculous images have long been overlooked because it is perceived that they are unskilfully executed and of minimal aesthetic value. But is art just about forming aesthetic judgements? Or is it about thinking through the different ways in which the visual impacts on us? Rosser and Garnett show very clearly that the latter, the dynamic relationship between an image and its viewers, is really the more compelling approach. Images which are deemed kitsch, poorly executed, or cheaply produced can exert a powerful influence on their viewers.

When I was a teenager, I spent a lot of time wondering whether a painting shut away in a cupboard for noone to see, still counted as art. The idea that art is something which enters into a relationship with its viewers is wonderful. It doesn't just validate the paintings which have long been denigrated as being of low aesthetic value. It validates the viewers. This perspective suggests that viewers themselves must be active participants in the artistic process; that their reactions make something 'art'. This is wonderfully liberating, and wonderfully egalitarian in its implications. Art is not just produced by skilled artists, but by everyone who responds to it. And this notion is taken to an extreme with the most original miraculous images, those described in Byzantium as 'acheiropoieton' - these were the images deemed not to be created by human hands, but by miraculous divine intervention - images which became 'art' as humans responded to their miracles.

The proactive and creative role for the viewer which miraculous images imply also made me wonder about how we paint the act of viewing in words and pictures. If viewing is itself something which participates in the artistic life of an object or painting, how to we depict that act? It is really striking that there are lots of images of miraculous images, and lots of stories about the operation of images (my favourite is a tale by the C13th Gautier de Coinci, wherein an irate and jealous miraculous statue of the Virgin Mary punishes a young man for giving a golden ring destined for her to another woman). These images and stories further underline the importance of viewing, since they take the viewers and their emotional responses as their subject. But in depicting this in a story or piece of visual art themselves, they create the beginnings of a kind of infinite regress, which I'm now continuing by talking about images of images being seen. It's a bit like endless hypertext commentaries on the act of reading, and it leads us deeper and deeper into the importance of human responses and the involvement of everyone in responding to, and creating, meaning.

Most thought-provoking, I thought, were the implications for how we think about images. Rosser and Garnett point out that many of these miraculous images have long been overlooked because it is perceived that they are unskilfully executed and of minimal aesthetic value. But is art just about forming aesthetic judgements? Or is it about thinking through the different ways in which the visual impacts on us? Rosser and Garnett show very clearly that the latter, the dynamic relationship between an image and its viewers, is really the more compelling approach. Images which are deemed kitsch, poorly executed, or cheaply produced can exert a powerful influence on their viewers.

When I was a teenager, I spent a lot of time wondering whether a painting shut away in a cupboard for noone to see, still counted as art. The idea that art is something which enters into a relationship with its viewers is wonderful. It doesn't just validate the paintings which have long been denigrated as being of low aesthetic value. It validates the viewers. This perspective suggests that viewers themselves must be active participants in the artistic process; that their reactions make something 'art'. This is wonderfully liberating, and wonderfully egalitarian in its implications. Art is not just produced by skilled artists, but by everyone who responds to it. And this notion is taken to an extreme with the most original miraculous images, those described in Byzantium as 'acheiropoieton' - these were the images deemed not to be created by human hands, but by miraculous divine intervention - images which became 'art' as humans responded to their miracles.

| Andres de Islas Mexico act. 1750s-1775 Our Lady of Guadalupe (Juan Diego Shows the Image to Bishop Zumarraga) , credit figgeartmuseum.org, also shown in Garnett and Rosser, p. 35. |

No comments:

Post a Comment